On October 14, the United States Supreme Court declined to review a challenge by the Liberty Counsel about the Florida Bar’s amicus brief in support of Martin Gill, a gay man who sought to adopt his two foster children. Gill made history last year when Miami-Dade Circuit Judge Cindy Lederman struck down a 32-year law prohibiting gays and lesbians from adopting. The Liberty Counsel claimed that the Florida Bar was not authorized to use membership fees in supporting ideological causes not related to the legal profession. The Supreme Court voted 5-2, and denied review of Liberty Counsel’s case, without comment.

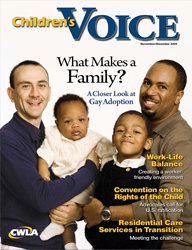

Gill and his partner of nine years have been foster parents to James*, 4, and John*, 8, since 2004 through the Florida Department of Children and Families, a CWLA member agency. But Gill isn’t a typical prospective parent in the eyes of federal law–he is a gay man seeking to adopt in Florida, the only state in the country that has an outright ban on adopting to homosexual parents.

With the legal backing of Florida’s American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Gill took his case to court. Child psychology experts testified that there was no scientific evidence that would support the state’s ban on gay adoption, and that it would be in the children’s best interests if they stayed with Gill and his partner. When Judge Lederman ruled the state ban unconstitutional and granted adoption rights to Gill, the case was seen as a huge milestone for gay and lesbian prospective parents in Florida, and for LGBT rights activists worldwide. The attorney general’s office, however, filed an appeal minutes after the decision. The case is now pending in the Third District Court of Appeals, leaving the Gill family waiting for a decision. The trial reignited a national debate surrounding gay and lesbian adoption.

Gay Adoption in Florida

A recent survey showed that there are 250,000 children in the United States living with gay and lesbian parents, according to Lambda Legal, a national organization dedicated to protecting the rights of the LGBT community as well as those with AIDS and HIV. The 2000 U.S. Census also showed that there are approximately 600,000 gay and lesbian families, and that they live in 99.3% of all U.S. counties. An upcoming 2010 U.S. Census will be conducted in March of next year and may bring greater clarity about these numbers.

Stephen and Joe Milano successfully adopted their children Alex and Ruben, in Texas. They were among the first adoption cases in a Dallas-based agency where the birth parent requested a gay adoptive parent for her child.

One of these families includes Steven Lofton, Roger Croteau, and their children. Like Gill, they tried to fight for their right to adopt in the state of Florida. The 2005 case, Lofton v. the State of Florida, was extremely publicized, with Rosie O’Donnell becoming one of their many staunch supporters. The case also reached the United States Supreme Court, only to have it dismissed as a “state issue,” and was sent back to the Eleventh Circuit District for further perusal.

Lofton and Croteau, both white pediatric nurses, were foster parents to HIV-positive Frank, Tracy, and Bert, who were all black, at a time in the 1980s when people were hesitant and scared of those afflicted with HIV/AIDS. The children have been with Lofton and Croteau since they were infants. Bert had been in their care since he was 2 months old; at age 3, he had seroreverted and tested negative for HIV. Once free from the virus, Bert was considered to be more adoptable. The state of Florida put him up for adoption, but refused Lofton’s request to adopt Bert because of the state ban on gay adoption. The family then moved to Oregon on the premise that Florida would release the children to Oregon’s state laws–until Florida decided to keep the three children as its wards.

Michel Horvat, a family friend and director of the Lofton-Croteau documentary We Are Dad, chronicled the family’s struggle for equal rights in adopting Bert, and the social stigma that ensued. Shot in a span of four years, the documentary closely followed the Lofton-Croteau family in their everyday routine. It also showed the underlying tension between the state of Florida and the family, even though they moved to Oregon, where they eventually adopted two other HIV-positive children, Wayne and Ernie, now 16 and 13. “I made a film about their lives to let the world know who these people were,” says Horvat. “They were a representation of a much bigger struggle that was going on.”

Although the Lofton-Croteau family is filled with love and mutual respect, a number of organizations decried the couple being adoptive parents, fearing for the safety and stability of the children. In truth, the family is like any heterosexual household; the parents drive their children to school, help them with their homework, ask them to help with the laundry, encourage volunteer work, and support them in their extracurricular activities.

Lofton and Croteau’s three eldest children, Frank, 22, Tracy, 22, and Bert, 18, now reside in Florida in order to receive state funding, but they have always been close with their extended family. All five of their children have always been exposed to female role models, such as their grandmother and their aunts. “It’s not just two guys and just a group of kids and a house,” Horvat says. Their family is large and well-rounded, with stable and loving relationships– from both male and female role models.

Challenging Traditional Roles

Based on Horvat’s four years of filming the Lofton-Croteau family, he challenges the arguments over a child needing both a father and a mother figure at home to grow up healthy and stable. For example, is the traditional family still a practical basis for the proper raising of a child? Or have the lines blurred between a mother’s role and a father’s role in a child’s life? What one equates as a mother’s role, such as cleaning the house and cooking meals, might be different for another household. The father might be the one staying at home and cooking, while the mother might be the one earning a salary for the household.

“Those paradigms are something of the past,” Horvat says. “Are you going to call your dad a ‘mom’ because he took out the trash, or because he took the kids to school that day? Is that a female role or is that a parental role?” The traditional mother-father paradigm has proven to be inconsequential in raising Lofton and Croteau’s children; the most important aspect of their family–and any family–is that as parents, they act in the best interest of their children.

A New Trend

When the Lofton-Croteau family’s struggle went public years ago, they experienced social stigma. But the once-hostile environment for gay and lesbian people in the United States is showing signs of improvement. According to the South Florida Sun Sentinel, three-quarters of Americans favor LGBT people’s right to marriage or civil unions based on a survey conducted by Harris Interactive last year. A staggering 69% of 2,008 adults surveyed believe gay people should be eligible to adopt. Compare these figures to a 2005 CBS/New York Times poll, where only 23% of interviewees believed that gays should marry, and 41% said that there should be no legal recognition of gay couples.

Legislature is following suit, with a recent bill proposed in October by U.S. Representative Pete Stark (D-Calif.) called the Every Child Deserves a Family Act. The bill will restrict funds to states that discriminate in their foster or adoptive programs based on marital status, gender identity, or sexual orientation.

Adoption agencies have also started shifting gears. According to the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute’s David Brodzinsky, 60% of more than 300 public and private agencies nationwide were willing to accept applications from gay and lesbian parents in a 2003 study he conducted. Brodzinsky says that 15% of the agencies he studied took “active steps” to recruit gay and lesbian parents, and over a third made placements.

Martin Gill at a rally for legislation in Tallahassee. He is currently waiting for the Florida court’s decision on his case to adopt his foster sons.

Houston residents Stephen and Joe Milano were among these families. They have been together for 18 years and raised their two children–Ruben, 8, and Alex, 6–since they were born. As Texas residents, they were able to adopt their two children from two separate agencies without legal constraints. Their inquiry at Adoption Advisory in Dallas proved to be a timely one. The day before the Milanos came to the agency, a birth mother had walked in with a special request; she wanted her baby to be adopted by gay parents. The Milanos’ case comprises a portion of the 15% of agencies in the U.S. that have had birth parents request gay or lesbian placements at least once, according to Brodzinsky. This became the tipping point for Adoption Advisory, which had once refused applications from gay parents; the Milanos became the agency’s first gay adoptive parents.

Actual or Perceived Harm?

While there are promising changes in the way gay adoption is being viewed and practiced, many people are still staunchly opposed to it. In the Gill and Lofton cases, organizations like the Liberty Counsel, American College of Pediatricians, and the Christian Coalition expressed reservations in court about allowing gay and lesbian people to adopt. Lawyers and experts of the state in the case against Gill presented reasons why children would be considered in danger if placed with gay or lesbian parents. They said that homosexuality would attract unnecessary social stigma to the children and that, scientifically, children could become homosexuals as well. Furthermore, they said that homosexual relationships were oftentimes unstable and insecure, thus likely prompting depression.

CWLA filed amicus briefs for both Lofton’s and Gill’s cases, citing that the ban on gay adoptive parents goes against well-established child welfare policies, saying every prospective family must be screened on an individual basis, to make sure they match the needs of the child. CWLA’s position statement with regard to gay and lesbian adoption reads that “lesbian, gay, and bisexual parents are as well suited to raise children as their heterosexual counterparts.” CWLA believes that by excluding gays and lesbians from the prospective resource parent pool, some children will not be afforded the privilege of having a permanent home. In 2008, there were 130,000 children waiting to be adopted, according to the Children Bureau’s Trends in Foster Care and Adoption report. Children waiting to be adopted were defined as those children with a goal of adoption and those whose parental rights were terminated.

Studies conducted by other experts have also countered the arguments of those opposed to gay adoption. Dr. Frederick Berlin, Associate Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, testified in Gill’s case against Florida. He says that with regard to children becoming gay because of having gay parents, “there is no evidence whatsoever to support that. If the sexual orientation of the parents was what would determine the sexual orientation of the children, then presumably we won’t have so many gay children growing up in heterosexual homes.”

Berlin stresses that based on decades’ worth of studies, the parents’ sexual orientation does not determine the sexual orientation of the child. “Anytime a child can grow up in a home where they have the love of parents… and can guide them and help them get off to a good start in life, that can be a good thing…whether in a homosexual environment or a heterosexual environment,” he says.

Dr. Stephen Erich, an Associate Professor in the University of Houston-Clear Lake, also did extensive research on the topic. His two-decade study on gay parents and their children is consistent with Berlin’s studies and concludes that there is no empirical evidence that would suggest that children growing up with gay parents would negatively impact their well-being. By conducting research on children ages 6 and 7, and on adolescents, Erich observed a myriad of variables that would help determine the state of the household. He studied the parent’s ability to get support from the community, family functioning, and the behavior of the children, among others. The study concluded that the children were doing well, and that the parents were able to sustain effective support networks. His study on 154 adoptive families and 210 adolescents yielded the same positive results. The teenagers were equally attached to their parents, whether they were gay or heterosexual.

Regarding a child’s likelihood for depression, both Berlin and Erich say that there has never been a study that has proven children with gay parents are prone to depression. However, both of them agree that children growing up in gay households would be more susceptible to harsh bias. “They may experience stress that is different or maybe even more than children growing up with straight parents, but it hasn’t shown that it has led to depression,” Erich says. He explains further that it would serve the children’s best interests if they were placed in permanent adoptive homes, regardless of the adoptive parents’ sexual orientation.

The Future of Gay Adoption

The Milanos have always been dedicated and supportive parents, but they weren’t without their share of raised eyebrows and prodding looks. “We got more stuff like that when [Ruben] was a baby,” Stephen says. People had tried to make sense of Stephen and Joe’s relationship when they were out with their sons, often staring and wondering if they were friends, or uncles, or something more, but overall they have not received extremely disparaging criticism. They are well-acquainted with people in their area, and know all the other parents in the community. Stephen admits that there have been people in their sons’ school who have tried to steer clear from them, but he doesn’t let it affect their family.

Their sons have begun to notice that their family is different from that of their classmates. Stephen explains to his children that every family is different, saying that one family has only one mom, another has just one dad, while another has a stepmom and another has a stepdad. Once, in kindergarten, Ruben’s friend noticed that he had two fathers. Parents usually drop their children off at school, and upon seeing his fathers, Ruben’s friend asked, “So, you have two dads?” Ruben said yes.

“No moms?” his friend prodded. Ruben said yes a second time.

“Cool!” the friend happily exclaimed.

The Milanos are like any other traditional family, in that they share a sense of respect and love for each other. They believe it’s not a question of who comprises the family, but a question of the value and depth of the relationships among the family members.

As for Gill, he is hoping every day that he’ll be allowed to keep his own family together. His case still sits in appeal, and the court posts its decisions online every Wednesday morning. “We’re just sitting here waiting. Any Wednesday at 10:30 [a.m.]…we could get a decision, in a month or three months,” Gill says. “I noticed on Wednesday mornings my behavior’s a little different. At first I didn’t know why, but I’m walking on pins and needles all Wednesday morning. After 10:30, I realize why.”

At the oral argument of appeal, Gill recalls that a judge had asked Deputy Solicitor General Timothy Osterhaus what would happen to the children should Judge Lederman’s decision be reversed and the ban be upheld. The response, as Gill remembers it, was that his children would be removed from his home and placed in another foster home, and that guardianship would not be option for him. “They would put the children up for adoption… and try to get them adoptive parents,” Gill said.

Despite the mounting apprehension in the wait for the court’s decision, Gill says that he and his family take life one day at a time. The family is making the most of their time together, with Gill constantly supporting his children in their gymnastics, tennis, and swimming lessons, joking that he is becoming more and more like a soccer dad. “I told myself I was going to treat them from that moment on like they were adopted,” he says of the initial decision. “We’re more of a family than ever.”

But for now, every Wednesday morning, he waits.

Maria Carmela Sioco is an editorial intern at CWLA.

Purchase this Issue

Other Featured Articles in this Issue

What Makes a Family?

A Closer Look at Gay Adoption

Residential Services in Transition

Agencies are meeting the challenge by using evidence-based practices and community-based care

A Child’s Rights

As the Convention on the Rights of the Child celebrates 20 years as international law, advocates call for U.S. ratification

Balancing Work & Life

How agencies can create a worker-friendly environment

Departments

• Leadership Lens

• Spotlight On

• National Newswire

• Down to Earth Dad

Parents should be wary of giving children empty praise

• Exceptional Children

Easy physical education adaptations for home and school

• CWLA Short Takes

• End Notes

• One On One

An interview with Lily Eagle Dorman Colby, Foster Youth Outreach Coordinator