Published in Children’s Voice, Volume 26, Number 1

by Courtney Fee

“They are children who will often have no opportunity for Head Start. Many will wait for months before they are assigned to public school. Those who do get into school may find themselves embarrassed by the stigma that attaches to the ‘dirty baby,’ as the children of the homeless are described by hospitals and sometimes perceived by their schoolteachers. Whether so perceived or not, they will feel dirty.”

—Jonathan Kozol, Rachel and Her Children

When Agnes Stevens first ran her hands over the pages of Rachel and Her Children, Jonathan Kozol’s

1987 book on families struggling with homelessness in America, her own selfhood felt at risk. She quickly learned, though, that this internal feeling of shakiness—stemming from retirement and a divorce—was far less severe than the plight of the nation’s 1.6 million homeless children battling for identity. The normality of childhood is lost when a youth is instead concerned with a next meal, which couch he or she is going to sleep on, and whether he or she will be able go to school the next day.

Stevens, a former teacher and nun, established School on Wheels in 1993 in a double-wide trailer in Malibu, California, to help offer stability to her local population of youth who were homeless and housing-challenged through one-on-one tutoring and educational preparation. Stevens dipped into her pension and income from private tutoring to cover the cost of books, school supplies, toys, and gas. With the help of generous friends, she used only $600 to get School on Wheels off the ground.

School on Wheels aims to enhance educational opportunities for K-12 children who are homeless, shrink the gaps in their education, and serve as a consistent support system during the trauma of housing instability. Ultimately, School on Wheels wants to help students feel cared about and focuses on the importance of obtaining a high school diploma. In 2015, more than 2,200 volunteers tutored 3,491 students.

Now, School on Wheels is concentrating on ramping up their digital learning initiative, thanks to a few large grants, and on developing a strategy to help families that are unsheltered—living in cars, campgrounds, RVs, or motels. “We can go into a shelter; we know the shelter staff and do outreach pretty easily. But to knock on motel doors or to go on campgrounds is a much more difficult endeavor,” says Executive Director Catherine Meek. For School on Wheels, success in the current political climate requires constant proactivity and reactivity.

School on Wheels’ learning center is based in the heart of downtown Los Angeles’s Skid Row district, which has the highest number of unsheltered homeless youth in the country. According to the Los Angeles Times, New York City traditionally reports the most homeless people in the country— primarily in its extensive shelter system—but Los Angeles consistently reports the highest number of people living in and around the streets. San Francisco, along with Los Angeles, New York City, Las Vegas, and San Jose, accounted for about a quarter of all unaccompanied youth in the country, a U.S. Housing and Urban Development report found, based on January 2017 numbers.

There are other nonprofits in the United States that engage in the similar mission of education for youth who are homeless. Some have even taken on the same name, like School on Wheels in Massachusetts or Indianapolis, forming in 2004 and 2001, respectively. Youth on Their Own in Arizona operates on the same plane but focuses more on financial assistance and the basic human needs of students who are homeless. Positive Tomorrows in Oklahoma concentrates on barrier removals for students who are enrolled yet housing-challenged by aiding with transportation, food, and basic needs. But for longevity and the sheer amount of volunteers committed to tutoring alone, School on Wheels takes the cake.

And statistics demonstrate the urgency for organizations like School on Wheels. California alone accounted for 21 percent of the nation’s homeless in 2015. Its major cities have something to do with those numbers: San Francisco may have the highest median income in the nation, but it also has the highest percentage of unsheltered youth who are homeless. Los Angeles may be the nation’s hub of entertainment-industry wealth, but there are 63,000 children who are homeless in Los Angeles County alone—and this only includes those who are enrolled in school.

Part of the CWLA approach to these issues is understanding that tackling youth homelessness is a holistic endeavor. “We tend to treat these issues and the children and families as if they are in individual silos. We need to work in a more collaborative way. We also need to better understand the relationship between and among homelessness, mental health, domestic violence, and stress,” says CWLA CEO Christine James-Brown.

As we move forward within the new presidential administration and into 2018, unanswered questions loom ahead. And with a rise in discriminatory policy-making, the proposed new budget, and ongoing attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, which would decrease health care opportunities for those in poverty, many child- and family-serving entities feel their jobs have just begun. Meek agrees. “It is incumbent not only on School on Wheels, but just about every nonprofit that I know, to expand our missions and certainly not narrow them,” she says.

It’s crucial that we protect those that are vulnerable by working beyond our means. We can no longer look to the missions of our own individualized nonprofits, the goals of our own parties, or the singularity

of our fundraising events. Looking for a way to help youth who are homeless and don’t know where to start? Meek believes the single most important thing is identifying homeless-serving organizations in one’s own community and volunteering. “Volunteer your time or volunteer your treasure,” she says.

Courtney Fee served as an editorial intern at CWLA in 2016 and 2017.

Purchase this Issue

Other Featured Articles in this Issue

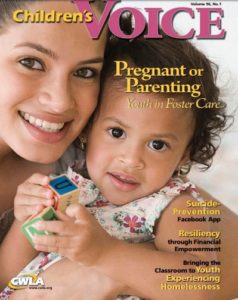

Addressing the Needs of Pregnant and Parenting Youth

A Lifeline in Your Pocket

Strategies for Long-Term Financial Success

Inter-Agency Collaboration for Change

Departments

Leadership Lens

Down to Earth Dad

Exceptional Children: Navigating Learning Disabilities and Special Education

One-on-One

Q&A with Alex Morales, CWLA Board Chair