By Kirk O’Brien, Yvonne Humenay Roberts, Kristen Rudlang-Perman, Crystal Ward Allen, and Peter J. Pecora

Nearly one in five children in foster care has been in care before. Reentry into care can lead to fractured families. Stable, nurturing families can bolster youth resilience and lessen negative long-term effects—but these protective factors can’t be nurtured if children keep re-entering care. While the number of children in foster care has decreased by nearly 25 percent since 2002, the percentage of children who have re-entered care has remained stable. In 2015, nearly 20 percent of children in out-of-home care—nearly 80,000 children—had been in care before, some more than once.

The high percentage of children who have been in care before suggest that youth and families aren’t receiving the support they need to remain together safely. Services and programs that better support families as they transition out of care could help. We know that most children in foster care develop physical, emotional, and/or behavioral challenges that can create significant ongoing concerns. These challenges often result from the parent’s or child’s unmet needs, and families require services and supports while the child is in care and after he or she leaves the system.

Before highlighting what agencies can do to support sustained permanency, it is instructive to outline what we know. First, keeping families together benefits children. The presence of consistency in family relationships has a positive influence on physical and mental health, education, and social development. Meanwhile, placement instability has the opposite effect. Second, the evidence base for “post-permanency” services is lacking. The California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare (CEBC) provides scientific ratings for child welfare programs. Of the five listed for post-permanency services, only one, Homebuilders,® has enough evidence to be rated (see here). While locally developed and implemented programs exist, most have not been evaluated extensively. Third, although the evidence base is lacking, there are core elements to existing services, including providing basic family resources, safety-focused and trauma-informed practices, caregiver supports and services and navigation services. Fourth, federal funding streams are fragmented, hard to braid together with local funds and compete with other priorities. Lastly, making sense of reentry data is a challenge as there is no consensus about the best indicator of reentry, or about what type of data should be examined (e.g., point-in-time versus an entry/exit cohort). (For more information on the above, see here).

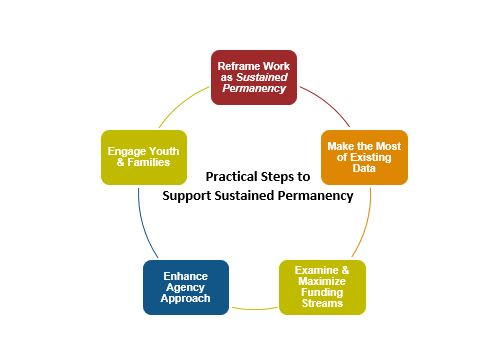

Ten practical steps agencies can take to support sustained permanency for families are presented after the diagram below, which subdivides steps across five domains:

Reframe Work as Sustained Permanency

- Reframe post-permanency (and reentry) work as sustained permanency. Describing this work as “preventing reentry” refers to the impact on the system, while “post-permanency” lacks the specificity of the purpose of the work. “Sustained permanency” focuses on maintaining the family and the value of practices and services provided by agencies.

Make the Most of Existing Data

- Explore different types of reentry data, including defining what success looks like. There are several types of reentry data. While point-in-time reentry data accurately reflects caseloads on a given day, it may be more informative to track reentry from a longitudinal perspective. The form that takes may vary and jurisdictions may want to use a broader definition than the narrow federal Child and Family Services Reviews (CFSRs) reentry measure (see here, p. 5). Additionally, more than one measure can be examined. Lastly, discussions of what success looks like for youth and families after they exit care need to take place.

- Identify predictors of reentry and sustained permanency. Variables that predict reentry measure(s) should also be carefully examined. Variables can include demographics of the child and family, reasons for entry, and time and experience in care—including the number of caseworkers, family and youth strengths, and more. Further, conducting multivariate analyses are essential to identify the drivers of reentry and sustained permanency because these analyses examine predictors in the presence of other predictors. Lastly, this work can also help identify sub-populations of youth (e.g., older youth) who may have specific needs.

- Create a sustained permanency dashboard with target goals. A dashboard with target goals shines a spotlight on critical outcomes the agency is trying to achieve. Crafting a visually appealing dashboard that tracks reentry data and critical predictors (drivers) for improvement helps assess progress.

Examine & Maximize Funding Streams

- Examine traditional and non-traditional funding streams to determine if financial support is being maximized. While sustained permanency efforts may compete with other priorities for federal dollars, it’s important to revisit federal funding sources to ensure they are being maximized. The same goes for local dollars. Additionally, non-traditional funding from philanthropies and social impact bonds can be included as a source of funding.

Enhance Agency Approach

- Establish agency values around sustained permanency. One way to draw more attention to sustained permanency is to revisit the values, beliefs, and attitudes held for this work. Are values documented (e.g., in a practice model) or do they need to be established? Training and ongoing coaching may be necessary to instill values agency-wide.

- Catalogue sustained permanency policies to determine if gaps exist. First, it is important to assess whether there are any sustained permanency policies (e.g., a functional assessment will be used every six months after exit from care to determine youth and family need). Once policies are identified, the next step is to see how they align with what the data tell us (e.g., about specific sub-populations) and how they align with established values. Existing policies need to be reviewed periodically to determine how they align with data, values and other areas.

- Catalogue sustained permanency services to determine if gaps exist. It is possible that there are gaps in services needed for many youth and families. Taking inventory of services available is an important step in determining if workers have access to needed services. It is also critical to map services onto different subpopulations to determine if gaps exist for specific groups of youth and families.

- Assess expertise and enhance coaching for sustained permanency. In many jurisdictions, there is good work happening to support sustained permanency. Jurisdictions need to identify expertise and try to spread those practices through job shadowing, coaching and other means.

Engage Youth & Families

- Engage youth and families around sustained permanency discussions. A critical component to all of this work is to meaningfully involve youth and families. Specifically, jurisdictions need to assess how youth and families can inform interpretation of data, define success, improve practices and support other families as they look to sustain permanency. Youth and family focus groups and/or advisory boards may need to be formed to provide a critical voice for how to improve sustained permanency services.

While a child welfare agency may be unable to take on all of these practical steps at once, prioritizing an area or areas to address first is a good starting point. There may be agencies and universities willing to support such work, as well. Adopting one or more of these practical steps can support youth and families as youth exit foster care and try to sustain permanency. Consequently, the number of youth in care who have been there before can be reduced from the current rate of one in five.

—————————–

Kirk O’Brien is a Research Director at Casey Family Programs, where he conducts, manages, and supports evaluation efforts to improve outcomes for youth and families.

Yvonne Humenay Roberts is a Senior Research Associate at Casey Family Programs and a licensed clinical psychologist. She conducts research in partnership with stakeholders to improve the health and well-being of children and families.

Kristen Rudlang-Perman is the Director of Data Analytics & Visualization at Casey Family Programs, where she works with both internal and external partners to use data strategically to inform child welfare practice and policy, with an emphasis on ensuring safe and permanent families for all children.

Crystal Ward Allen is Strategic Consultant at Casey Family Programs and has worked in child welfare and juvenile justice for over 35 years, working for safe children, strong families and supportive communities.

Peter Pecora has a joint appointment as the Managing Director of Research Services for Casey Family Programs and as a Professor in the School of Social Work, University of Washington, where he has worked with state departments of social services in the United States and in other countries to design and evaluate risk assessment systems for child protective services, intensive home-based services, and foster care programs.