Featured Article: How can adoption fit into a social worker’s personal life without overlapping with his or her professional career?

By Jennifer Michael and Madeleine Goldstein

Last fall, Tara Moser bumped into another social worker at a hospital health fair. An infant adoption specialist at a private agency, the social worker told Moser she had more newborn babies than she had adoptive parents. “It stuck in my head,” says Moser. She and her husband couldn’t get pregnant naturally, and they had decided not to try infertility treatments. They considered adopting a baby, but originally dismissed the idea because Moser owns a play therapy practice in Cape Coral, Florida, that has a foster care contract. She wanted to keep her work life and her personal life completely separate.

Moser went home from the network-ing event and talked to her husband. By December, they had finished filling out adoption paperwork. In March, the social worker called Moser and said a baby boy was born who happened to look exactly like Moser and her husband. They took him home when he was a week old, and the adoption was final in July.

“Being a social worker has impacted raising him,” Moser says. “I’m very big on attachment parenting, especially with the adoption cases I work with.” To increase bonding, she gives her son massages, carries him in a sling close to her heart, and spends every moment she can with him. For the first six months, she took him to work with her every day. She now has a nanny, but Moser still takes her son to the office when she does paperwork or goes to staff meetings. “He attached almost instantly,” she says. “We literally do everything together.”

Because Moser had helped clients go through the adoption process, she knew what to expect with her son’s adoption. “I wasn’t as scared,” she says. “Having that leg-up was helpful.”

Across the country, social workers like Moser are becoming adoptive parents. “Lots of social workers adopt,” says Adam Pertman, executive director of the Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute. “For social workers, it’s often an easier road–not because they have to do any less filling out of paperwork, but because they understand it better.” While no one interviewed for this article had any solid data about the number of social workers who become adoptive parents themselves, anecdotally, Pertman sees it happening.

When Moser adopted her son, she did everything she could to make sure there was no conceivable conflict of interest in her adoption process. She adopted him from a private agency that she had no affiliation with, and since the father of one of her employees is a local judge, she made sure the adoption case wasn’t on his docket. “I wanted everything completely separate,” she says. “We dotted our i’s and crossed our t’s so there was no question.”

But not everyone so deeply considers the ethical issues involved when a social worker adopts a child. Frederic Reamer, a social worker who has adopted children himself, has consulted on a handful of cases around the country where social workers have worked with a child, become attached to that child, and wanted to adopt the child. “On the one hand, what a magnanimous thing for a social worker to open her or his heart and home to a child,” says Reamer, who has written books on ethics and social work and chaired the committee that wrote the code of ethics for the National Association of Social Workers. “At the same time, those situations can be fraught with ethical questions.”

For example, he says, if a social worker is writing reports to a court to influence terminating the parental rights, then that social worker shouldn’t adopt that child because the social worker’s desire to parent the child might cloud or influence his or her judgment. Reamer explains that many agencies just won’t allow a social worker to adopt a child they have worked with. While some agencies will permit a social worker to adopt a child, several have protocols to ensure that the social worker has not had any direct involvement in the child’s case. “They would want there to be a bright line between the social worker’s involvement,” Reamer says. “A firewall.”

Most of the social workers Reamer’s known who have considered adopting a child they worked with have not gone through with the adoption. “This doesn’t happen that often,” he says.

Gayle Ward, a senior social worker for Kinship Center in Carmel Valley, California, says sometimes other social workers frown when she says her children were originally on her caseload. “It’s unusual,” she says. “But I did the right thing.” Ward first met the brother and sister who she would eventually adopt when they were 2 and 3 years old. “I have never fallen in love with anyone on my caseload the same way,” she says. She told her husband she really wanted him to meet the kids. “My husband said, ‘It’s your job to take care of many kids, not bring them home.'”

At that time, she didn’t follow her heart and try to adopt the siblings because she felt it would be ethically wrong to cross that boundary and become too intimately involved with them. Another family adopted the children and they would occasionally send Ward cards and pictures. Ten years later, the adoptive parents called Ward and told her they had given up. The children were acting out, and the parents couldn’t handle it, so they asked the juvenile courts to take them back. The girl was living in a group home, and the boy was back in foster care.

“I was carrying them around in my heart from the time I met them, and kicking myself from here to everywhere that I hadn’t acted on my emotions when they were [first] in foster care,” Ward says. She became a licensed foster parent in a nearby county where she doesn’t work, and she adopted both children when they were teenagers. “My husband said to me, ‘I knew they’d come someday,'” she says. “When you have that kind of feeling in the heart, you should be brave enough to challenge the systemic belief not to get too involved.”

Ward was honored this year as an Angel in Adoption by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute. “It was the best thing we’ve ever done,” she says. “It was the hardest thing we’ve ever done in terms of trying to help them heal.”

The majority of social workers who adopt, though, do not adopt from their own agency, but they do use their professional knowledge to help their own families. Deborah Siegel, a professor of social work at Rhode Island College, has attended workshops for social workers who are also adoptive parents. “There are so many of us who do it,” says Siegel, who specializes in adoption and has adopted two daughters with her husband, Reamer. Siegel says that the workshops she’s attended discuss what it’s like to work in adoption and live in it too.

Libby Slaton, a 37-year-old social worker in Malvern, Arkansas, spent 11 years training foster parents. She’s currently in the process of adopting a 4-year-old girl. “It’s much different when they live with you–you’re having to practice what you preach,” Slaton says. She didn’t want her 9-year-old biological daughter to be an only child, but she didn’t want to have another baby. “My husband and I knew we did not want to start completely over,” she says. “We did not want to start with midnight feedings again.”

The little girl they are adopting was in several foster homes before coming to the Slatons, and she had some aggression and difficulty expressing her needs. “We had a really rough period in the beginning,” Slaton says. “But with consistency, patience, and love, she’s really doing well.”

Like Slaton, Caren Sue Peet is a social worker and adoptive mom. Peet has devoted her life to helping other children get adopted because of her own experience adopting children. Peet helps adoptive parents every step of the way. She has a poster board in her living room in Smithtown, New York, with pictures of the 2,000 babies she’s helped place. “Some were born last week, some were born 17 years ago,” Peet says.

She tells anxious potential parents not to be nervous and to relax, and she shares her own story with them. Peet was born with a genetic condition called neurofibromatosis, in which nerve tissues grow tumors. Since there was a 50% chance that she would pass her condition on to a baby, she decided to adopt her two children instead. “The whole process was really overwhelming,” she says.

She met a potential birth mother, but a week before the baby was born, the birth mother changed her mind. “I just sat and cried,” Peet says. “To me, it was like having a stillborn. That was my baby. We named him, his name was going to be Matthew–which means ‘gift from God.'” Weeks later, Peet was introduced to a 17-year-old girl in Louisiana, whose mother said that if she had the baby, she had to move out of the house. But after the boy was born, the grandmother changed her mind, and said they could both stay. So, Peet lost another baby. “I was in terrible grieving,” she says.

But eventually, Peet received a call that a baby boy had been born in Queens, New York. She took him home when he was five days old and named him Justin. Since Justin’s birth mother was from Paraguay, Peet decided she wanted his younger sibling to look like him. “I knew if I had a blond, blue-eyed baby, he would feel different,” she says.

When her son was 4 years old, Peet adopted his baby sister, Heather, from Guatemala. It took six months of bureaucratic paperwork, letters to members of Congress, and Peet flying to South America and pleading with the U.S. Embassy to process the paperwork to get her daughter’s Visa and take her home. “That was really hard knowing she was waiting for us and we couldn’t have her,” Peet says. Now she encourages and inspires other adoptive parents, volunteers, and advocates for orphans.

Last year, she collected 4,200 pairs of socks for orphans around the world. “I hate when my feet are cold,” she says. “It just drives me crazy.” So, when she is helping a family adopt from an orphanage oversees, she sends 100 pairs of socks with them to take to the kids. She was recently honored for her efforts by being named an Angel in Adoption by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute. “I live and breathe adoption,” she says. “I wanted to make the adoption experience be a wonderful experience for people.”

It can be difficult to separate work as a social worker with being an adoptive mom, says Dr. Judith Lee. “Your child really needs a mother. You can be a social worker to everybody else’s child,” says Lee, who has a PhD in clinical social work. When she and her husband tried to adopt a baby in New York 25 years ago, adoption agencies turned them away because Lee is Jewish and her husband is Chinese. “We weren’t the same,” she says. Because of Lee’s own difficulty adopting a baby, she spent 15 years running a warm, welcoming adoption agency. She now works with private adoptions, telling parents to never give up hope because they will find their baby.

That’s the attitude Lee took in finding her own children. When she and her husband were turned away by adoption agencies, she took out her high school and college yearbooks and wrote letters and made phone calls to everyone she had ever known asking them to help her find a baby. A friend of a friend knew a bookkeeper in an attorney’s office in South Carolina who was pregnant and didn’t want to keep her son. Lee adopted the Italian-Israeli boy as an infant. Eight months later, Lee received a phone call from another friend of a friend of a friend who knew a woman who was having a baby girl, who was going to be one-fourth Chinese. The pregnant mother liked the idea of the baby having a Chinese father.

Lee and the birth mother of her second child became close friends during the last months of her pregnancy. “I really, really loved her,” Lee says. “She and I both cried with one another, sharing with one another. We were both incomplete women: I was unable to have a baby, and she was unable to take care of a baby.” The birth mother asked Lee to promise to give her baby girl art and music lessons. Lee said that was something she would do anyway. Years ago, Lee and the birth mother lost touch, but her daughter is now studying opera in Zurich. Her daughter said to her one day, “We kept the promise, didn’t we Mommy?”

Purchase this Issue

Other Featured Articles in this Issue

Social Workers Who Adopt

How can adoption fit into a social worker’s personal life without overlapping with his or her professional career?

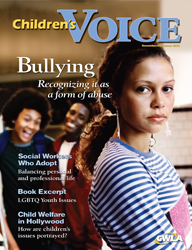

Mean Girls and Boys

Recognizing bullying as a form of abuse

Hollywood Spotlight

Is the portrayal of child welfare in movies and television helpful or harmful?

A Call for Organizational Transformation

Excerpt from CWLA’s new book, LGBTQ Youth Issues

Departments

• On the Road with FMC

• Leadership Lens

• Spotlight On

• National Newswire

• Working with PRIDE

Updating the PRIDE Family Development Plan

• Down to Earth Dad

Is there ever too much parenting?

• CWLA Short Takes

• End Notes

• One On One

An interview with Kathleen Pelley, CWLA author