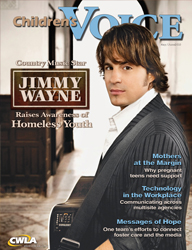

Featured Article:Foster child turned country music star walks across America to raise awareness for Homeless Youth

Jimmy Wayne, a 37-year-old rising country music star, didn’t always have a spotlight shining over him. His dark childhood was marked with abuse, abandonment, and instability. With his mother in and out of prison, he bounced around a series of foster homes, ultimately becoming homeless as a teenager. His life began to turn around when a North Carolina couple named Russell and Beatrice Costner gave him a stable home and a chance to start over. He used their support–and the solace of a guitar–to bolster himself into a successful music career. Since 2003, several of his songs–including “Stay Gone,” “I Love You This Much,” and “Do You Believe Me Now”–have soared to the Top Ten on the Billboard country charts.

On New Year’s Day, Wayne embarked on a six-month walk halfway across America, from Nashville, Tennessee, to Phoenix, Arizona. He launched the Meet Me Halfway campaign to raise awareness for homeless youth. He spoke to Children’s Voice in the early morning from Canyon, Texas, just before beginning his day’s walk up Route 66 heading toward Albuquerque, New Mexico.

How did you decide to start your Meet Me Halfway initiative?

It was very simple. I was turning up the heat in my house and I was stirring a cup of coffee, just relaxing, and there was a feeling that came over me. It was almost like a guilty feeling. I started thinking about the people who were responsible for me being able to turn my heat up and pour a cup of coffee. It just reminded me that I really didn’t do very much last year in 2009, because I was very busy on tour and my time was very limited.

I thought I could do a walk across America, and I got to thinking about how insane it was. I thought, ‘If I think it’s insane, someone else is going to think it’s insane; and when they think it’s insane, they’re going to talk about it.’ And that’s how we’re raising awareness [about youth homelessness]. By doing this walk, we get people talking about it.

So it started as a kind of a guilty feeling about turning up the heat. When you’ve been there–living on the streets–those are the kinds of things you don’t take for granted. Simple things like putting your clothes in the washer–some folks don’t have to think about that twice. But I am proud of my washer because I remember not having one. You never forget those moments.

You’ve talked about accepting help on your walk, because you want to encourage people to offer help to homeless youth. Why is this important to you?

When I accept people’s help, I Tweet about it and talk about it. I think that encourages people who may be afraid to help others out there. When I say ‘a person gave me a place to stay tonight and they didn’t even know me,’ I think that helps people understand that it’s just that simple.

In other interviews, you talk a lot about the Costner family, who helped you so much growing up. Looking back, who else played a role in your success?

Carla Moore Foy was my social worker. I can’t imagine how difficult it must be for social workers to do their job every single day and love it. They can’t possibly love doing that job every day, because the results aren’t always what they wish for the kids, and it’s got to be discouraging. I’ve talked to social workers; I’ve played concerts for them, just to say thanks. They always tell me that [they’re] just so glad to see somebody like [me] who made it through the system.

What was important for me was having a social worker like Carla who didn’t give up. She was just so strong and just didn’t give up. When you’re a kid, you’re angry and sometimes you just lash out, you let go, you give up. But when you have somebody like Carla around you who was there regardless–that was really helpful for me.

Jimmy Wayne recently walked through Amarillo, Texas, as part of his Meet Me Halfway campaign.

A provision of the Fostering Connections to Success Act would allow foster care to be extended to age 21 as long as the teen meets educational requirements. What might this extension mean for teen homelessness?

I know that when I moved in with that family, I was so far behind, it took me two years or so to catch up. If they had kicked me out at 18, I was still so far behind. Even by the age of 21 you’re still just getting your stuff together. But boy, those three years really can make a huge difference. I know from experience if you give someone three years, well–that’s almost enough time to get a bachelor’s degree. That would make a big difference in a kid’s life.

It’s the right thing to do–there’s no way around it. Why should we give up on a kid when they’re 18 years old? It just doesn’t make sense to me.

When you were growing up, you went to 12 different schools in a span of two years. What would you say to children and youth going through similar circumstances?

Its not what I’d like to say to the kids, it’s what I’d like to say to the adults–to the people that can make a difference in their lives. Because if the kids could do it on their own, they would have done it. They would have already accomplished whatever we’re going to tell them they should accomplish. They need our help getting there. The main thing that they need is a launching pad. They need a place to stay. They need a secure home for at least a year of their life.

The analogy is that if a hurricane hits Florida, you don’t go to Florida to raise funds for Florida, because they don’t have any. You go somewhere else to raise funds. So when I talk to kids, I say, ‘Stay strong, follow your dreams,’ but they’ve heard that a million times. It’s like, ‘Okay, follow my dreams, but how am I supposed to do that when I’m living on the street? What am I supposed to hold onto? I don’t have anything to hold onto–I’m homeless.’ So what you do is, you go to the people out there who haven’t been struck by the hurricane, so to speak, and you ask them to help these kids. They’re the ones we should be talking to.

How has music influenced your ability to cope with your childhood?

It’s definitely a therapeutic exercise for me. I started writing poems when I was 12 years old and that was to vent–to release all the frustration in my mind. I was a very depressed teenager and I really didn’t care, because I thought I wasn’t going to be living long anyway.

I saw a convict from a local prison at our school. He got on stage and played his guitar and called it country music. He said, ‘I’m singing the story of my life, this is a country song that I wrote.’ And I never forgot that. I thought, ‘If he’s playing country music, that’s what I’ll play. Because my story is similar to his.’ And then I started putting my poems to the music. I went out and got a guitar that weekend.

Music has always been an outlet for me. I write songs about my story. They don’t always get heard… not a lot of folks want to hear about you living on the street. It doesn’t appear that way anyway. But the people that do hear them connect to them, and it lets me know that I’m doing the right thing. I’m writing songs about my life, about the stories that I know that thousands of people out there can relate to–either personally or vicariously. If they know someone who’s been in a foster home or if they’ve been in a foster home.

Country star Jimmy Wayne gathers with supporters. As a former homeless teen, Wayne is walking halfway across America to raise awareness for homeless youth.

What do you bring with you while you’re walking every day?

I’ve started carrying these crosses that have been donated to me by fans and Twitter followers. A foster kid, an 18-year-old kid in Arkansas, had been moving around from home to home trying to find places to sleep at night. He saw me walking and asked me why I was walking. I told him, and it really just brought tears to his eyes because he’s the kind of kid that I’m walking for. He liked this cross that I had on my backpack, and I gave it to him.

My Twitter followers heard about it, and I’ve had one lady stop me on the side of the road and give me 27 cross necklaces. I’m collecting crosses every day almost. It’s gotten to the point where I can’t wear them, so I’m holding onto them until I get to Phoenix where I can distribute them.

Who has been the most memorable person you’ve met on the walk so far?

It goes back to that little town in Arkansas; I always go to this one story. Marcy is a lunchroom lady who serves food to the kids. [In the years she’s worked there,] she’s taken in 10 kids from that school. She’s let them come to her house and sleep on the couch or whatever they need, just to help them out. She and her husband live in a trailer and she doesn’t have much of anything. But she’s helping these kids out–she has turned their lives around. Her story is just so inspiring, because it just proves that you don’t have to be rich to help someone.

The kid who asked me for the cross–he was one of the kids that she’d taken in. It’s a very small town and you wouldn’t think that it being a small town like that, that there would be any kind of homeless situation, but there is. It’s everywhere–not just in the cities.

Purchase this Issue

Other Featured Articles in this Issue

Q&A with Country Music Star Jimmy Wayne

Former foster child walks across America to raise awareness for homeless youth

Young Mothers at the Margin

A commentary on why pregnant teens need support

Messages of Hope

Fostering Media Connections encourages journalists to write about the foster care system

Choose Your Own High-Tech Adventure

Multisite agencies make technology work for them

Departments

• Leadership Lens

• Spotlight On

• National Newswire

• Working with PRIDE

Implementing PRIDE internationally

• On the Road with FMC

• Exceptional Children

Creating positive parent-teacher relationships

• CWLA Short Takes

• End Notes

• One On One

An interview with Linda Spears, Vice President, Policy and Public Affairs